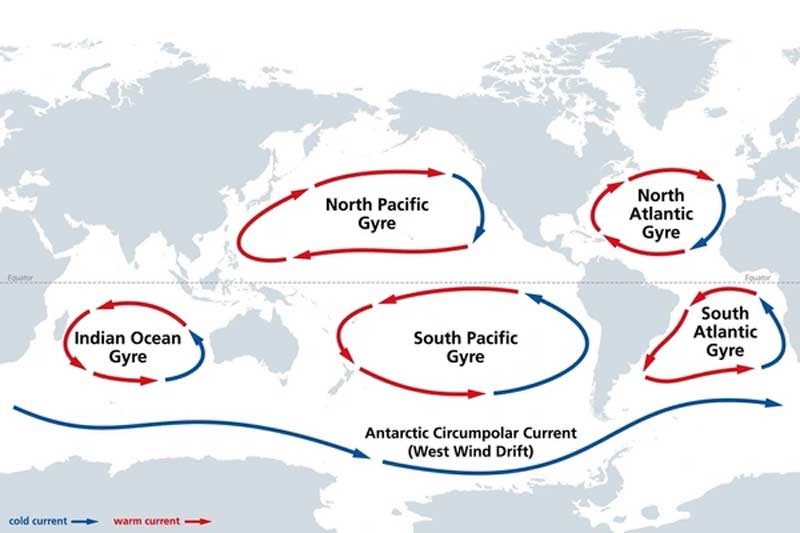

The types of oceanic gyres provide important information about ocean movement and its consequences on the planet. Wind patterns and the Earth’s rotation push large, round water structures known as oceanic gyres. We classify them into subtropical gyres, which dominate mid-latitudes, and sub-polar gyres, located near the poles.

What is Oceanic Gyres:

The large, circular-moving loops of water that are driven by the major wind belts of the world are called gyres.

Types of Oceanic Gyres:

There are two types of gyres,

- Sub-Tropical Gyres

- Sub- Polar Gyres

Sub-Tropical Gyres:

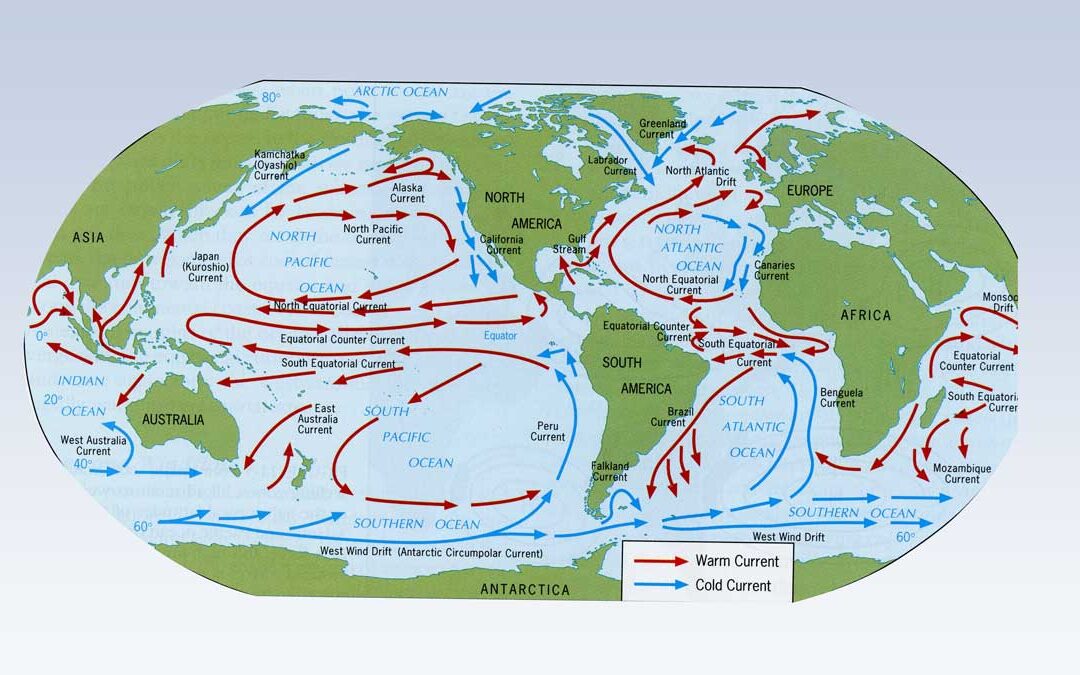

There are four major subtropical gyres, as shown in the figure. Generally, each subtropical gyre is composed of four main currents that flow progressively into one another.

Equatorial Currents:

The trade winds, which blow from the southeast in the southern hemisphere and from the northeast in the northern hemisphere, set in motion the water masses between the topics.

Western Boundary Currents:

When equatorial currents reach the western portion of an ocean basin, they must turn because they can not cross land. The Coriolis effect deflects these currents away from the equator as western boundary currents, which comprise the western boundaries of subtropical gyres.

Northern or Southern boundary currents:

Between 30 and 60 degrees latitude, the prevailing westerlies blow from the northwest in the southern hemisphere, from the southwest in the northern hemisphere, and from the southwest in the northern hemisphere. These winds direct ocean surface water in an easterly direction across an ocean basin.

Eastern Boundary Currents:

When currents flow back across the ocean basin, the Coriolis effect and continental barriers turn them toward the equator, creating an eastern boundary current of subtropical gyres along the eastern boundary of the ocean basins.

Sub- Polar Gyres:

The prevailing westerlies eventually push northern or southern boundary currents that flow eastward into sub-polar latitudes at about 60 degrees north or south latitude.

Here, the polar easterlies drive these currents in a westerly direction, producing sub-polar gyres that rotate opposite to the adjacent subtropical gyres. Sub-polar gyres occupy smaller areas and are fewer in number than subtropical gyres.