Grouting plays a crucial role in geotechnical engineering by improving the strength, stability, and impermeability of soil and rock foundations. Engineers inject a fluid-like material into voids, cracks, or porous zones to seal, consolidate, or reinforce the ground. Different grouting methods apply depending on subsurface conditions and engineering needs.

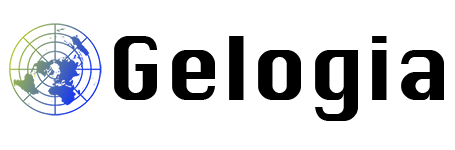

Types of Grouting:

The major grouting processes used to treat defects in rocks and porous overburden materials include:

- Curtain Grouting

- Consolidation Grouting

- Blanket or Area Grouting

- Contact Grouting

- Special-Purpose Grouting

Curtain Grouting:

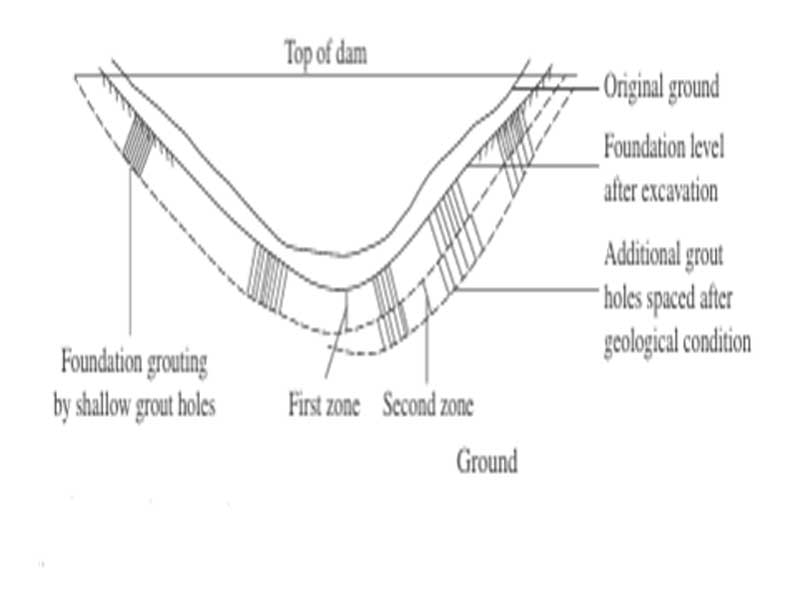

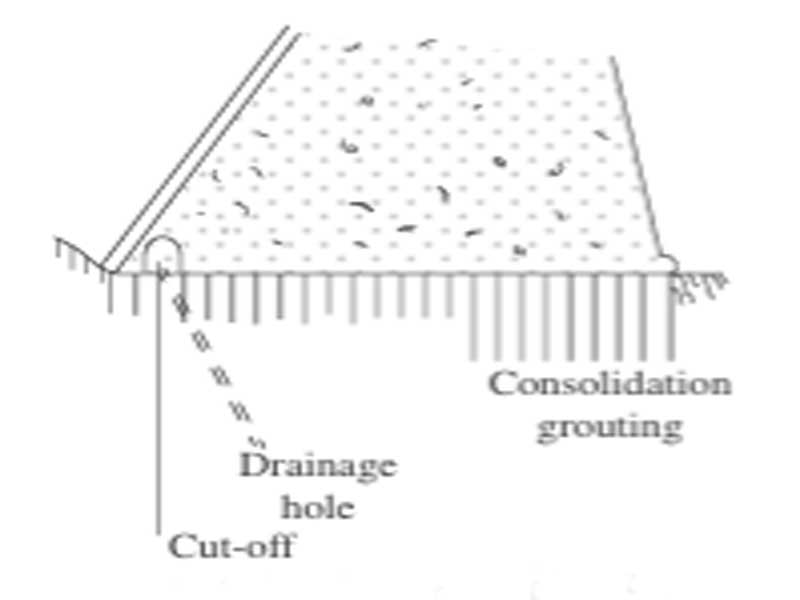

Engineers widely apply curtain grouting in dam and reservoir construction. They drill and grout through one or more lines of holes in the foundation to specified depths to cut off seepage under dams or other structures, creating a barrier that blocks water paths. Typically, grout holes run parallel to the dam axis or perpendicular to water flow (Fig.1).

Fig.1: Profi le along dam axis prior to foundation cover showing foundation treatment by curtain grouting

A common rule of thumb sets the curtain grouting depth at two-thirds of the dam’s hydrostatic head. Rock cores and water percolation tests at the site help determine the depth of fissured and porous zones. When site data is insufficient, Wahlstrom (1974) suggests grouting to one-third the dam height plus 15 m depth.

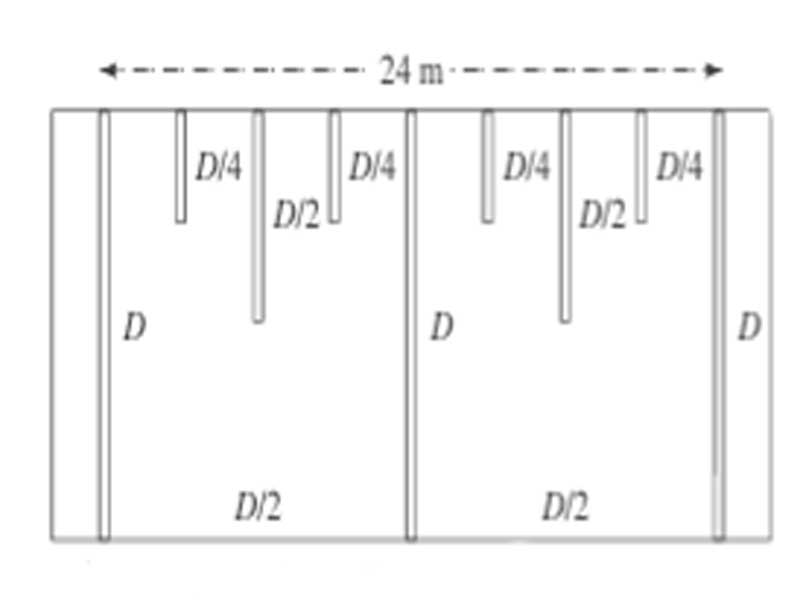

After completing initial grout holes at fixed intervals, engineers drill more holes in between, gradually reducing the height until grout intake diminishes near the closure (Fig.2).

Fig.2: Depths D of grout holes in relation to dam height in closure pattern

Consolidation Grouting:

Consolidation grouting strengthens loose rock masses by injecting grout. Engineers perform it over fractured and permeable foundation rocks, usually targeting shallow depths (Fig.3). The grout solids settle into voids, sealing fractures and consolidating the rock to enhance strength.

Fig.3: Profile across dam axis consolidation grouting of foundation rocks

They carry out grouting after dam foundation excavation, not post-construction, fixing hole locations based on geological mapping. If clay seams appear in the foundation rock, workers excavate them before grouting to improve effectiveness.

In extremely fractured or seamy rocks, excavation might be necessary to remove weak zones before grouting. To avoid grout wastage through open joints, engineers first apply low-pressure single-line grouting along the foundation perimeter to seal leakage paths.

Blanket or Area Grouting:

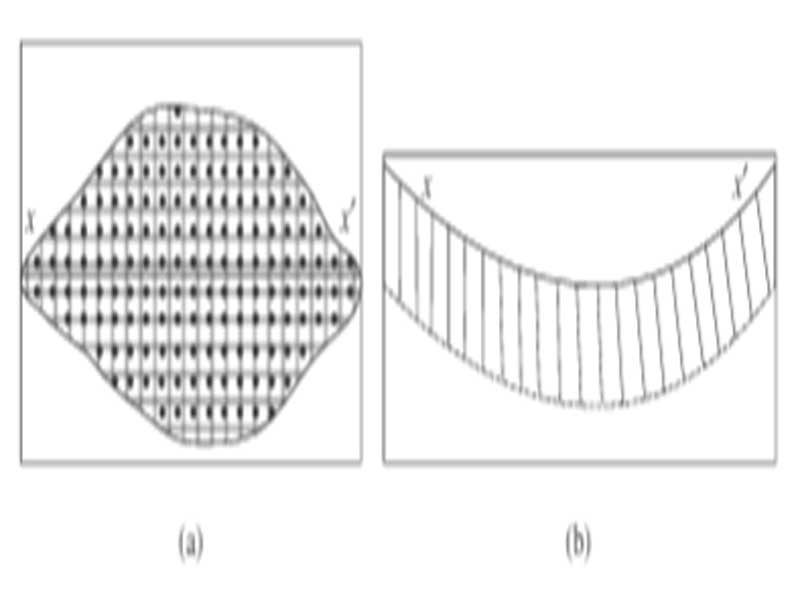

Engineers apply blanket grouting over a specified shallow area to seal voids in unconsolidated materials or fractures in rock, such as in dam foundations or reservoir surfaces. They focus on the top few meters where defects due to porosity or fracturing appear.

They drill grout holes usually between 6 to 10 meters deep from the foundation or ground surface (Fig.4). Grout holes run normal to the surface but may angle to intersect bedding or joint planes in steeply dipping rocks. They always perform blanket grouting before dam construction or reservoir filling.

Fig.4: Blanket grouting of dam foundation: (a) plan of the dam showing grout holes arranged in a grid pattern; and (b) section along dam axis (x–x’) showing grout holes extended from foundation to subsurface strata restricted generally to 10 m

Contact Grouting:

Contact grouting seals gaps and strengthens the bond between engineering structures and foundation rock by injecting neat cement grout at their interface. Shrinkage of concrete causes voids and seepage paths along this contact, which the grout fills to stop leakage.

Engineers commonly use contact grouting between concrete dams and abutment rock or along the crown of lined tunnels to create watertight bonds. During construction, they may install header pipes in concrete at contact points and grout through them after raising the structure. Alternatively, they drill holes for grouting after construction completes.

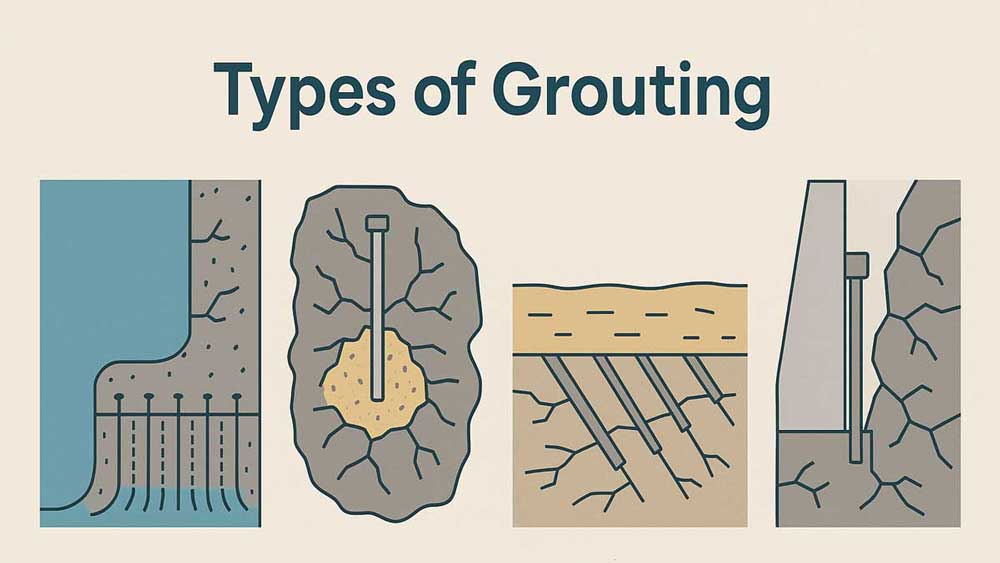

Special-Purpose Grouting:

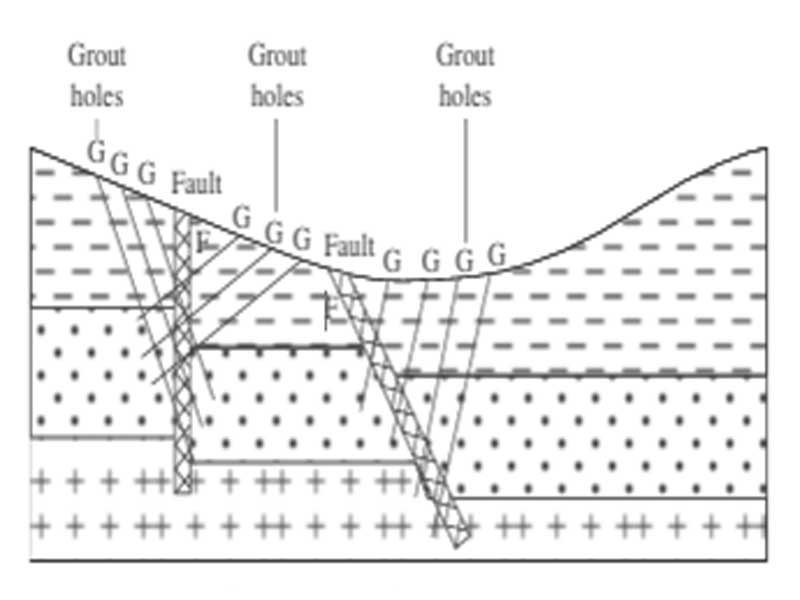

Engineers perform special-purpose grouting to treat adverse geological conditions, such as fault zones or highly fractured zones at depth, or to stabilize subsurface materials around shafts or deep structures.

They design special-purpose grouting plans based on exploratory investigations that evaluate geological structure geometry and the extent of weak zones. For example, to grout a vertical or steeply inclined fault zone, they drill closely spaced, inclined holes that intersect the fault plane (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Special-purpose grouting—treatment of fault zones (F–F) by injecting grout through inclined holes (G)

When sealing fine fissures in dam or tunnel concrete, engineers use chemical grouts because of their superior penetration properties.