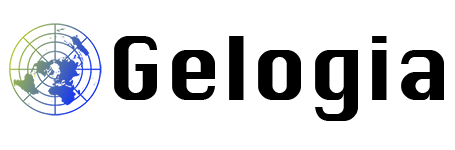

The formation of soils begins as a natural geological process that breaks down rocks into finer particles. Weathering — both mechanical and chemical — gradually turns solid rock into loose, fertile soil that supports plant life.

Formation of Soils:

Soil refers to a natural aggregate of mineral grains, with or without organic constituents, that people can separate by gentle mechanical means such as agitation in water. In contrast, rock forms a natural aggregate of mineral grains held together by strong and permanent cohesive forces.

Weathering breaks down rock by decreasing the cohesive forces that bind mineral grains, causing large rock masses to disintegrate into smaller and smaller particles. The parent rock undergoes weathering, which results in soil formation. Mechanical disintegration and/or chemical decomposition usually drive this process.

Mechanical Weathering:

Mechanical weathering breaks rocks into smaller particles through agents like the expansive force of freezing water in fissures, sudden temperature changes, and abrasion by moving water or glaciers.

Temperature changes with enough amplitude and frequency expand and contract the volume of rocks in the superficial layers of the Earth’s crust. This volume change creates tensile and shear stresses that eventually fracture even large rocks.

This type of weathering occurs significantly in arid climates, where extreme atmospheric radiation causes sharp temperature variations between sunrise and sunset.

Wind and rain continuously erode rock surfaces. Growing plant roots crack rocks apart by exerting force in voids and crevices.

Chemical Weathering:

Chemical weathering (decomposition) transforms hard rock minerals into soft, easily erodible matter. The main types of decomposition include hydration, oxidation, carbonation, desilication, and leaching. Oxygen and carbon dioxide in the air react with rock elements when water is present.