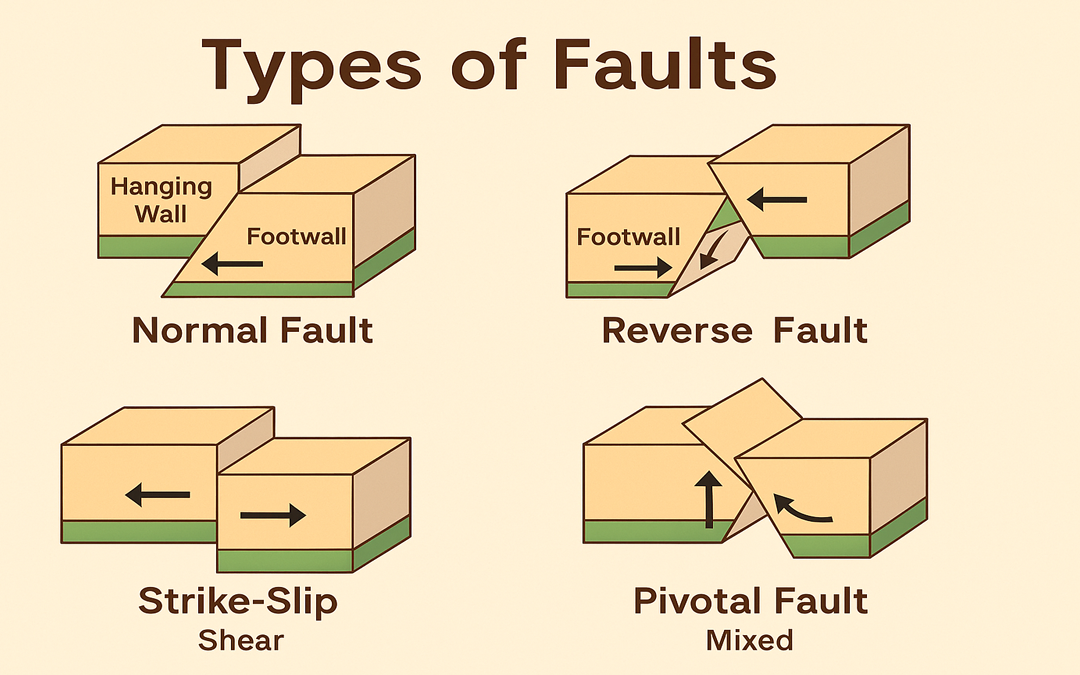

Faults are fractures in the Earth’s crust where blocks of rock have moved past each other due to tectonic forces. These movements are caused by stresses such as compression, tension, and shearing. Understanding the types of faults is essential in geology to interpret earth movements, earthquake activity, and the structure of rock formations.

Different Types of Faults:

The following is a description of the different types of faults depending on the nature of displacement:

Normal Fault:

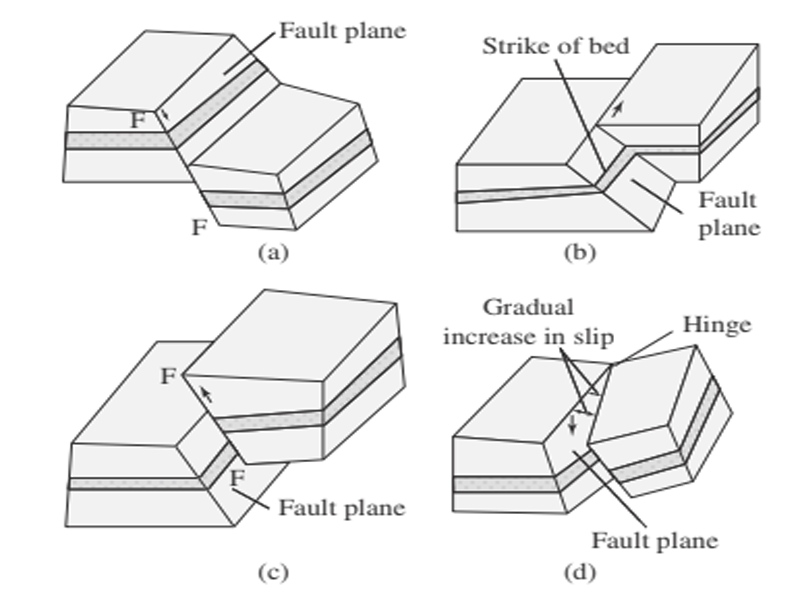

Normal fault is the simplest type of fault in which the hanging wall block moves downwards, relative to the footwall block, see Fig. 1(a). Tectonic movement of the earth’s crust may give rise to normal faults. The tensional stress is responsible for the displacement of crustal blocks in a normal fault.

This kind of fault typically occurs in regions where the Earth’s crust is being stretched or extended. As a result, normal faults are often seen in areas experiencing divergent tectonic activity, such as mid-ocean ridges or continental rift zones.

Reverse Fault or Thrust:

In reverse fault or thrust, the movement of the crystal block is such that the hanging wall moves upwards relative to the footwall, see Fig. 1(c). This fault brings about salient changes in the rock mass. If the fault plane slopes at an angle of more than 45°, it is up-thrust. If it is less than 45°, it is over-thrust.

In the over-thrust, the hanging wall actually moves over the footwall. It is the reverse in the case of under-thrust when the footwall is pushed under the hanging wall. A very low angle (nearly horizontal) thrust is called nappe.

Reverse faults are typically found in regions of compression stress, such as at convergent plate boundaries, where two tectonic plates push against each other. These faults can create major geological features like mountain ranges.

Strike-Slip Fault:

In strike-slip fault, shown in Fig. 1(b), the movement is essentially horizontal under the action of shearing stresses. This type of fault is associated with folding and tearing. Figure 3.15(c) shows a strike-slip reverse fault where the movement is both in the strike direction also horizontal which makes the right-hand block to move upwards.

Strike-slip faults are often found at transform plate boundaries, where plates slide past one another horizontally. A well-known example is the San Andreas Fault in California.

Pivotal Fault:

In a pivotal fault, two blocks are joined at a certain part as a pivot. It appears like a normal fault on one side of the pivot, whereas on the other side it is a reverse fault. The interface between the two blocks is the pivotal part. The term hinge fault denotes the type of fault in which the relative displacement of the two blocks increases away from one end of the fault, which acts as the hinge of the two blocks, see Fig. 1(d).

Pivotal faults show complex movement patterns and are relatively rare, but they help geologists understand mixed fault behavior in areas experiencing variable stress directions.

Conclusion:

Each type of fault represents a different kind of movement and stress in the Earth’s crust. From the downward movement of normal faults to the upward and horizontal shifts in reverse and strike-slip faults, these structures help shape the surface of our planet. By studying the types of faults, geologists gain valuable insights into tectonic activity, earthquake behavior, and landscape evolution.