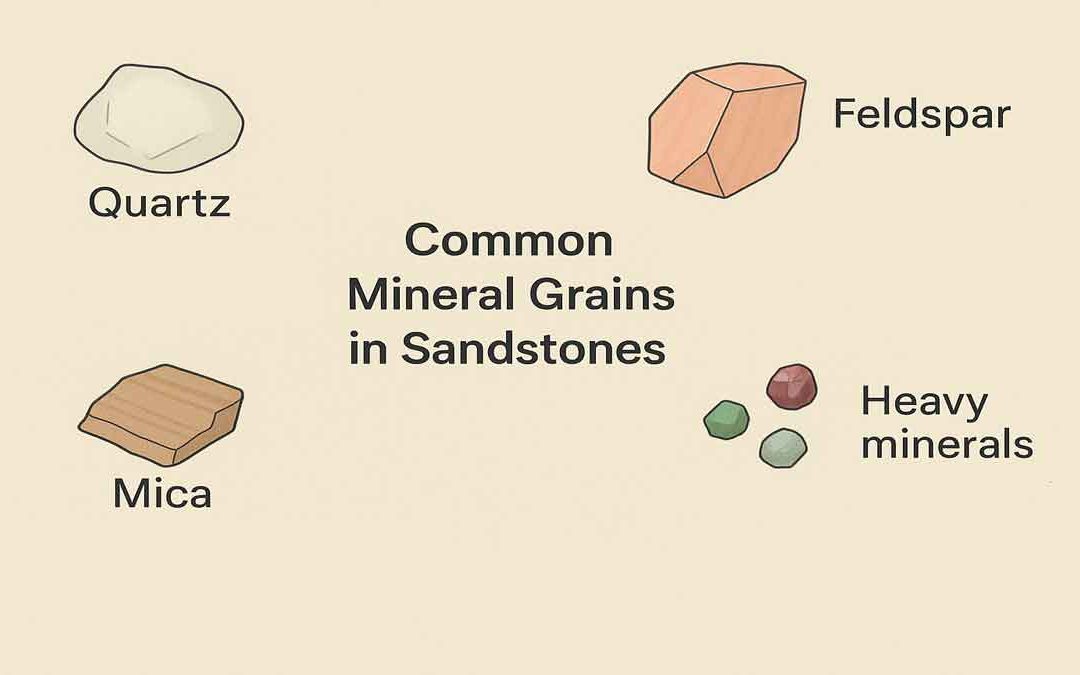

Mineral Grains in Sandstones:

A very large number of different minerals may occur in sandstones, and only the most common are described here.

Quartz:

Quartz is the commonest mineral species found as grains in sandstone and siltstone. As a primary mineral, it is a major constituent of granitic rocks, occurs in some igneous rocks of intermediate composition, and is absent from basic igneous rock types.

Metamorphic rocks, such as gneisses, formed from granitic material, and many coarse-grained metasedimentary rocks contain a high proportion of quartz.

Quartz also occurs in veins, precipitated by hot fluids associated with igneous and metamorphic processes. Quartz is a very stable mineral that is resistant to chemical breakdown at the Earth’s surface.

Grains of quartz may be broken or abraded during transport but with a hardness of 7 on Mohs’ scale of hardness, quartz grains remain intact over long distances and long periods of transport. In hand specimen quartz grains show little variation: coloured varieties such as smoky or milky quartz and amethyst occur but mostly quartz is seen as clear grains.

Feldspar:

Most igneous rocks contain feldspar as a major component. Feldspar is hence very common and is released in large quantities when granites, andesites, gabbros, as well as some schists and gneisses, break down.

However, feldspar is susceptible to chemical alteration during weathering and, being softer than quartz, tends to be abraded and broken up during transport.

Feldspars are commonly found in circumstances where the chemical weathering of the bedrock has not been too intense and the transport pathway to the site of deposition is relatively short.

Potassium feldspars are more common as detrital grains than sodium and calcium-rich varieties, as they are chemically more stable when subjected to weathering.

Mica:

The two commonest mica minerals, biotite and muscovite, are relatively abundant as detrital grains in sandstone, although muscovite is more resistant to weathering.

They are derived from granitic to intermediate composition igneous rocks and from schists and gneisses where they have formed as metamorphic minerals. The platy shape of mica grains makes them distinctive in hand specimen and under the microscope.

Micas tend to be concentrated in bands on bedding planes and often have a larger surface area than the other detrital grains in the sediment; this is because a platy grain has a lower settling velocity than an equant mineral grain of the same mass and volume so micas stay in temporary suspension longer than quartz or feldspar grains of the same mass.

Heavy minerals:

The common minerals found in sands have densities of around 2.6 or 2.7 g cm3 : quartz has a density of 2.65 g cm3, for example. Most sandstones contain a small proportion, commonly less than 1%, of minerals that have a greater density.

These heavy minerals have densities greater than 2.85 g cm3 and are traditionally separated from the bulk of the lighter minerals by using a liquid of that density, in which the common minerals will float, but the small proportion of dense minerals will sink.

These minerals are uncommon and study of them is only possible after concentrating them by dense liquid separation. They are valuable in provenance studies because they can be characteristic of a particular source area and are therefore valuable for studies of the sources of detritus.

Common heavy minerals include zircon, tourmaline, rutile, apatite, garnet and a range of other metamorphic and igneous accessory minerals.

Miscellaneous minerals:

Other minerals rarely occur in large quantities in sandstone. Most of the common minerals in igneous silicate rocks (e.g., olivine, pyroxenes, and amphiboles) are too readily broken down by chemical weathering. Oxides of iron are relatively abundant. Local concentrations of a particular mineral may occur when there is a nearby source.