Sedimentary basins are morphotectonic depressions on Earth’s crust, which accumulate a considerable amount of sediments over geological time. Sedimentary basins are the repositories of a great volume of economic deposits, including hydrocarbons, coals, groundwater, and many mineral and metal deposits.

Study of basin analysis covers the basin formation mechanisms, sedimentation style of the basin, the evolution of a basin with time due to the changing tectonic regime, and its ultimate destruction. Detailed study of sedimentary basins is necessary for the successful exploitation of different types of deposits of economic deposits.

Categories of Sedimentary Basins:

Basins were earlier known as geosynclines. Sedimentary basins are classified considering its plate tectonic context. Primary aspects of classification and evolution of basins are, a) whether a basin is formed on an oceanic crust or on a) continental crust, b) proximity of the basin to a plate boundary and c) the nature of the nearest plate boundary.

Basins form in all three types of crustal stress environments i.e. extensional, compressional and strike-slip settings. In extensional regimes the axis of maximum stress is vertical and in both compressional and strike slip regimes the axis of maximum stress is horizontal.

Five broad categories of sedimentary basins are recognized which are as follows (Busby and Ingersoll, 1995).

- Basins in divergent settings

- Basins in an intraplate setting

- Basins in convergent setting

- Basins in transform and transcurrent fault setting

- Basins in hybrid setting

1. Basins in divergent setting:

These basins form because of extensions, and these are broadly divided into two types,

1.1 Terrestrial rift valley basins:

Rifts within the continental crust bounded between high-angle normal faults are known as terrestrial rift valley basins. These are broadly classified into two types- passive rift and active rift. In the case of a passive rift, extension causes the basin to form, which is unrelated to the mantle plume and triple junction.

Active rift involves crustal extension caused by the upward movement of a mantle plume and the formation of a triple junction. The proportion of bimodal volcanics is significant in the case of active rifts. Terrestrial rift valley basins may evolve into ocean basins with continued rifting and drifting over a period of a few million years.

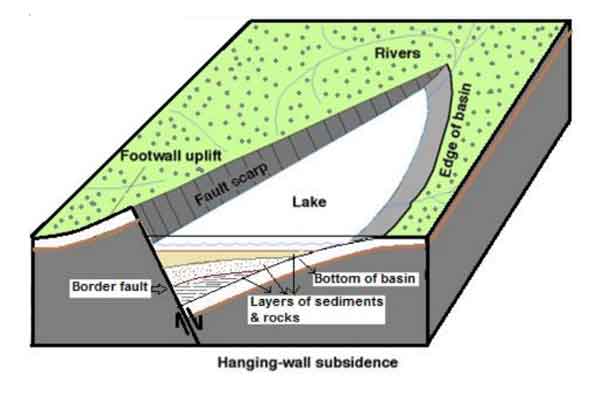

A common example of a terrestrial rift valley basin is a half-graben, which is flanked by a high-angle extensional fault on one side and ahanging wall dip slope on the other side (Fig. 1). Most of the sediments are supplied by the hanging wall dip slope. The footwall scarps supply localized fan-shaped conglomeratic deposits. The basin may be a few tens of km wide and a few hundred km in length.

Fig. 1 Sketch of a half-graben basin (modified from Schlische, 1995).

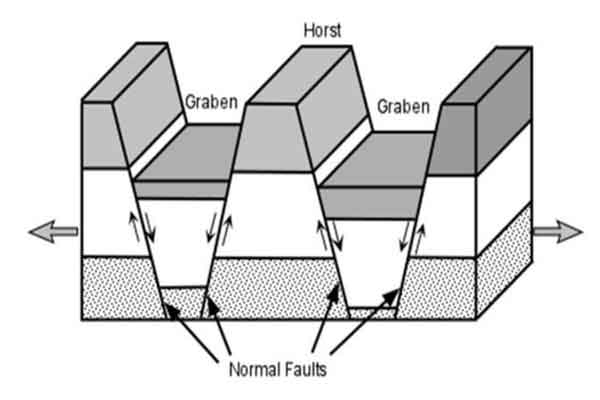

Terrestrial rift valley basin may also involve a series of horst and graben structures, bounded by normal faults on both sides (Fig. 3). Horsts or highs indicate the elevated portions of the basin, while the grabens indicate depressions.

The ‘Bombay High’ represents a horst-like structure on the basement. The thickness of Cenozoic sediments is much higher within the grabens compared to the horsts. At present, there is no active terrestrial rift valley basin in India. Modern rift basins are found in East Africa.

Fig. 2 Three-dimensional view showing horst and graben structures in a terrestrial rift valley basin

1.2 Proto-oceanic rift troughs:

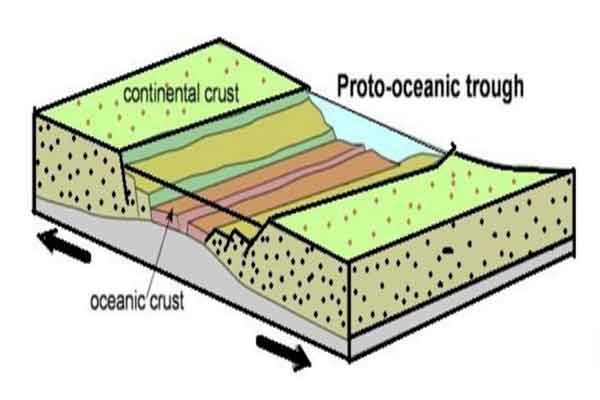

These are incipient oceanic basins floored by a new oceanic crust and flanked by young, rifted continental margins (Fig. 3). This type of basin indicates a transitional stage between terrestrial rift valley basins and passive margin basins.

They form because of the continued extension of the rift basin. They are characterized by the presence of an incipiently developed oceanic crust in the axial portion. The Red Sea is an example of a proto-oceanic rift trough.

Fig. 3 Sketch showing a proto-oceanic basin (sketch modified after Nichols, 2009).

2. Basins in intraplate setting:

These basins occur inside a plate and are situated away from plate boundaries.

2.1 Intra-cratonic basin:

Intracratonic basin occurs within the cratonic areas. Origin of this type of basin is controversial because of the stable nature of the craton. It may be associated with a fossil axial rift in cases. Broad convex-downward basins are also known as sag basins.

Thermal subsidence is significant in case of sag basins. Vindhyan, Kaladgi, Cuddapah, Chhattisgarh and Bastar basins belong to this category.

2.2 Passive margin:

A passive margin represents the transition between a continent and an ocean, which is not an active plate boundary. It represents a mature rifted continental margin at continent-oceanic interface.

Passive margin occurs at every ocean-continent boundary that is not marked as a subduction zone or strike-slip fault. The subsidence of this basin increases gradually toward the deep ocean side. Passive margins define the east and west coast of India, which are further classified depending on the occurrence of basinal highs.

2.3. Active ocean basin:

These are oceanic basins whose volume either increases or decreases with time. Atlantic is an example of an active growing ocean basin since it has passive margins on both sides. The Pacific is an example of an active shrinking ocean basin as subduction zones occur on both sides.

2.4 Dormant ocean basin:

These are ocean basins floored by non- spreading and non-subducting oceanic crust. These basins are floored by oceanic crusts, which neither spread nor subducts and therefore they maintain their volume. Gulf of Mexico is the largest dormant ocean basin.

3. Basins in convergent setting:

Basins in convergent margins may be of various types depending on the nature of plates involved in the subduction, i.e. ocean-ocean, continent-continent and ocean-continent. Variation in the angle of subduction is also an important factor.

3.1. Trench:

A trench is an elongated deep trough formed on the subducting oceanic plate. It represents the deepest sedimentary basin. This type of basin occurs in the Andaman area.

3.2. Trench slope basin:

The local structural depression formed on the subduction complex is known as the trench slope basin. This type of basin occurs in the Andaman area.

3.3 Fore-arc basin:

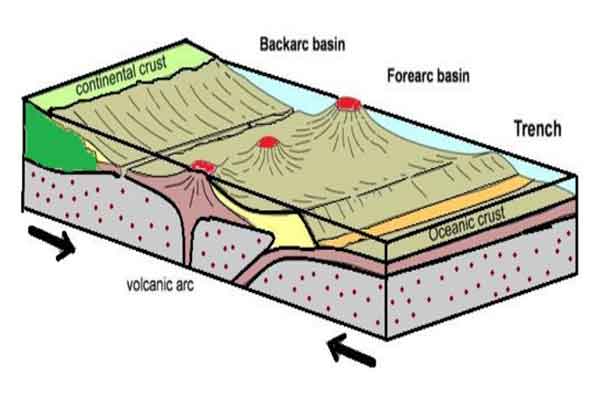

This basin occurs within the arc-trench gap. Sediments are supplied to this basin mostly from the magmatic arc (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Cross section showing trench, fore-arc and back-arc basin (modified from Nichols, 2009).

3.4. Intra-arc basin:

Extensional back-arc basins form where the angle of subduction of the down-going slab is steep and the rate of subduction is greater than the rate of plate convergence.

3.5. Back-arc basin:

Fore-arc basins form behind intra-oceanic magmatic arcs in oceanic basins and behind continental magmatic arcs in continental basins when foreland fold thrust belts are absent. A steep subduction angle causes this type of basin to develop, as the subduction rate exceeds the plate convergence rate. This type of basin occurs in the Andaman area.

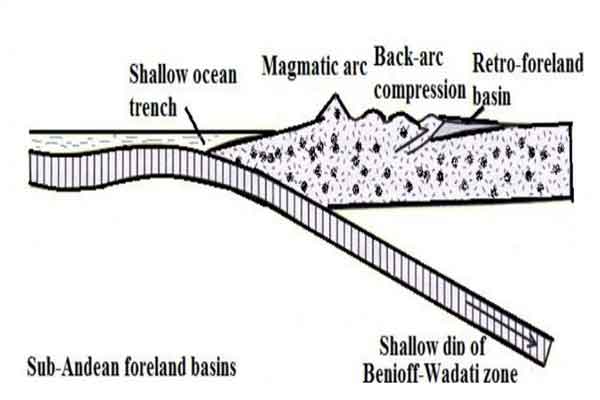

Fig. 5 Retro-arc foreland basin (modified from Decelles and Giles, 1996).

3.6. Retro–arc foreland basin:

A foreland basin forms parallel to a mountain belt. A gentle angle of subduction (Fig. 6) allows plate convergence to exceed subduction, leading to compression and the formation of this type of basin. The Andes region of South America contains such basins.

Geologists call these basins retro-arc foreland basins because they form behind the arc. In the case of a retro-arc foreland basin, the thrust belt’s tectonic load generates the basin, whereas a fore-arc basin results from crustal thinning. In this case, the subduction zone’s angle is much gentler than that of a fore-arc basin.

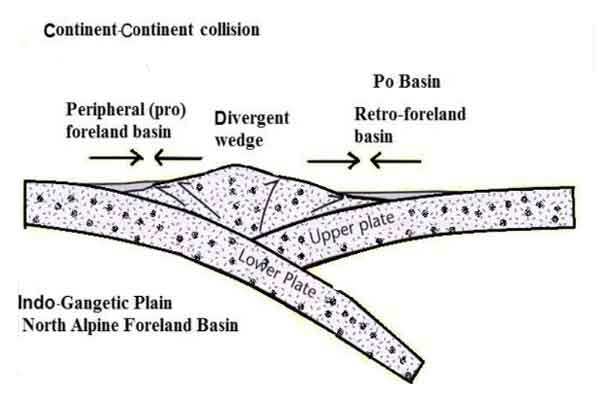

3.7. Peripheral foreland basin:

The subducting plate contains peripheral foreland basins (Fig. 7). The thrust belt’s tectonic loading creates this type of basin. The width and depth of the basin depend on the load amount and the flexural rigidity of the foreland lithosphere. A lower flexural rigidity of the lithosphere and a higher load amount result in a deeper basin.

In contrast, a higher flexural rigidity and a lower load amount create a shallower basin. The foredeep refers to the deepest part of the basin. Examples of this type of basin include the Ganga and Punjab basins.

Fig. 6 Idealized model for peripheral foreland basin (modified after Decelles and Giles, 1996).

3.8. Piggyback basin:

It is a type of minor depression developed on top of a thrust sheet as part of a foreland basin system. The basin is separated from the fore deep by an anticline or syn-depositional growth structures.

3.9. Remnant ocean basin:

It is a type of shrinking ocean basin caught between a colliding continental margin and/or arc-trench system, and ultimately subducted or deformed with suture belt e.g. Bay of Bengal.

3.10. Foreland Intermontane Basin:

It is a type of basin formed within basement uplifts in foreland settings.

4. Basins in transform and transcurrent fault setting:

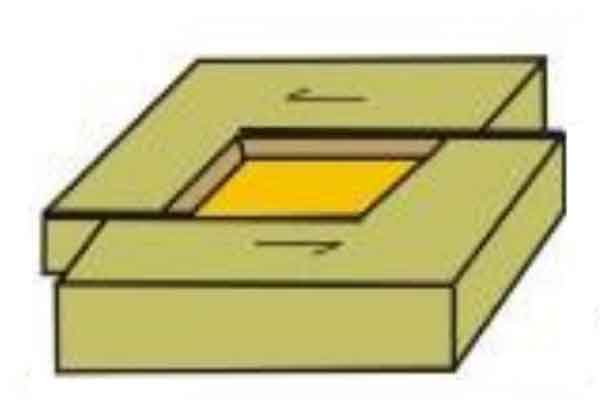

4.1. Transtensional basin:

The overlap of two separate strike-slip faults may create regions of extension, which forms pull-apart basin (Fig. 8). This type of basin is typically rectangular or rhombic in plan and is deep in nature.

4.2. Transpressional basin:

This type of basin forms in the localized zones of compression along a strike slip fault system.

4.3. Transrotational basin:

This type of basin is formed by rotation of crustal blocks about vertical axis.

Fig. 7 Sketch of a pull apart basins showing strike-slip faults.

5. Basins in hybrid setting:

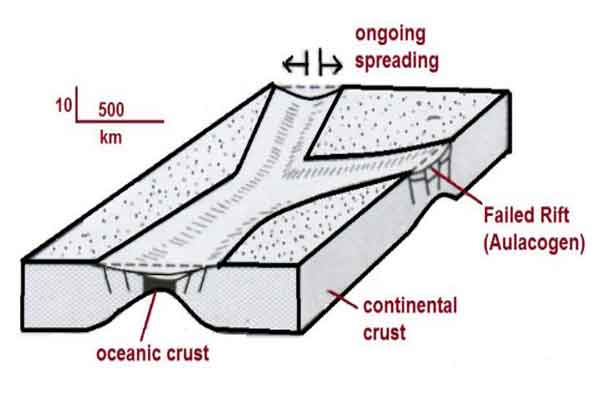

5.1 Aulacogen:

A failed arm of a three-armed rift system formed the basin, while the other two arms continued evolving to create ocean basins (Fig. 8). The basin extends from the margins into the interiors of cratons. It is wider near the sea and narrows toward the land. The Cambay Basin exemplifies an Aulacogen.

Fig. 8 Failed rift and aulacogen in RRR (rift-rift-rift settings) (modified after Einsele, 2000)

5.2. Intra-continental wrench basin:

It is a complex type of basin formed within continental crust due to distant collisional process.

5.3. Impactogen:

It is a type of rift basin formed at high angles to orogenic belts without pre-orogenic history e.g. Baikal Rift.

5.4. Successor basins:

Formed in intermontane settings following the cessation of local orogenic nephrogenic activity, e.g., Southern Basin and Range Province.